As a designer or developer, accessibility should be a top priority when it comes to branding and design. Accessibility is not only a moral obligation, but it can also benefit your business and attract a wider audience. In this session, you’ll learn how to make your designs accessible to everyone, including those with disabilities.

Colleen discussed how accessibility applies to branding and design, and why it’s important to consider it in your work. You’ll also get familiar with color accessibility guidelines, learn how to check contrast, and test for color blindness. By incorporating accessibility into your designs, you’ll not only make a positive impact on your community but also enhance your skills as a designer or developer.

Watch the Recording

If you missed the meetup or would like a recap, watch the video below or read the transcript. If you have questions about what was covered in this meetup please tweet us @EqualizeDigital on Twitter or join our Facebook group for WordPress Accessibility.

Read the Transcript

>> AMBER HINDS: All right, we are at 7:05, so I’m going to go ahead and get us started. If you’ve just joined, feel free to continue introducing yourself, saying hello in the chat. We’re going to go through some announcements and then, of course, get to our main event with our speaker, Colleen Gratzer.

So if you’ve never been before, I have a few announcements that I want to share. The first is that we have a Facebook group called WordPress Accessibility. If you just search “WordPress Accessibility” on Facebook, you can find it. Or you can go to “Facebook.com/Groups/WordPress.accessibility.” And that is the best way to connect with other attendees in between meetups, share what you’re working on, get feedback, get plugin recommendations, answer code questions, or ask code questions, any of those sorts of things. So please join the group if you are a Facebook user.

We always get asked whether or not this meetup is being recorded. Yes, it is being recorded. It will be available in about two weeks. We get corrected captions and a full transcript, and then we will make the recording available on our website.

You can find upcoming events and recordings from all of the past meetups at “equalizedigital.com/meetup”. That is where this recording will be posted when it is available.

You can also join our email list if you are interested. It’s at “equalizedigital.com/focus-state,” and that’s the best way to get notified of upcoming events. We send out reminders the day before… I think, like, a week before, maybe, about events. And we also send, a couple of times a month, a newsletter that has a link to all of the recaps and recordings, and some news from around the web that is relevant to WordPress and Accessibility. So please consider joining the email list.

If you are interested in listening to the episodes, we are now turning them into podcasts upon requests from some attendees, so you don’t have to watch them on YouTube. You can listen to them on your podcast player of choice. Our podcast is called “Accessibility Craft.” If you go to “accessibilitycraft.com”, then you can find the podcast and the meetup recordings that are available there.

We haven’t gotten all of the past episodes out because we only started doing this at the beginning of this year, but all of the recent ones are there. We’re going to try and find some time to also add in some of the past ones as well as we’re able to.

We are looking for sponsors for the meetup. The WordPress Foundation unfortunately does not have funds available to cover the cost of the live captions or for the post-event transcription. So they have told us that if we want to have these, we have to go out and find sponsors on our own.

So if your company is interested in sponsoring and helping to make this meetup accessible for everyone, please reach out to myself or Paula, our co-organizer. You can reach us at “meetup@equalizeDigital.com.” That’s our email address and it will go to both of us. There’s also information on the website about sponsorship, but we can send that to you as well.

You can also email us if you’re interested in speaking or if you have other suggestions for the meetup; ways that you would like to see it improve, or topics that you would like to see covered. Even if you’re not going to be the speaker, if you’re just, like, ”I really want to learn about this. Can you find a speaker for it?” We could try our best to see if we know someone who could talk about that topic. So feel free to reach out to us if you would like.

Who are we? I’ve said our email a bunch of times and our websites, so I’m not going to say it again. But if you’re not familiar, my name, of course, is Amber Hinds. I’m the CEO of Equalize Digital. We are a certified B Corp and a member of the International Association of Accessibility Professionals, and we are focused on WordPress accessibility. It’s our goal to make the web as accessible for people as we possibly can, for people of all abilities.

We have a WordPress plugin called Accessibility Checker. We are actually going to be running a sale, so this is my mini pitch, for Global Accessibility Awareness Day later this week. If you’re interested in trying it, there is a free version on “Wordpress.org” that you could use free forever. It’ll do unlimited posts and pages. But if you are interested in upgrading to Pro, we’re going to have a 30% off from May 18th through the 24th with coupon code “GAAD23.”

We have a couple of upcoming events. Oh, I should also say, there were no sponsors today so I am your sponsor today, which is why I gave you a little commercial [chuckles] on my plugin because we are covering the cost of live captions.

We have a couple of upcoming events. The first one is a special off our normal calendar of the first Thursday and third Monday. For Global Accessibility Awareness Day, we’re going to have a panel discussion. Myself, my partner, Steve, will be coming on with Nick Corbett [phonetic] from Carol Center [phonetic] for the Blind; and Tanner [phonetic] from Accessibility Officer [phonetic] just to talk about building accessibility into websites.

If you have questions, you want to have an opportunity to talk to either someone who is blind, someone who runs projects, or a developer, we kind of have all of that covered on the panel, so feel free to come and get questions answered. That will be this Thursday, May 18th, at 04:00 pm, Central Time, and you can get the registration link on the meetup page.

Then our next regular meetup will be on Thursday, June 1st, at 10:00 am Central, and that topic will be “Accessibility on a Deadline: Strategies for Meeting Standards.” And then we have another off-the-normal calendar event coming up on Wednesday, June 14th.

For those of you who tried to tune into our first Thursday meetup, you might have seen or you definitely saw that our speaker, unfortunately, had some technical issues and was never able to get into Zoom, so we ended up having to reschedule that meetup. So that meet-up with Stefano [phonetic] was rescheduled for Wednesday, June 14, at 10:00 am Central time. And that’s when you can learn about accessible fluid typography in the block editor.

So I am very excited to… Well, I don’t know what I just did, sorry. OK, I think I got it. [chuckles] …To find you here, Colleen, and add a spotlight. There we go. Hopefully, they can see you. So I’m very excited to introduce our sponsor… It is one of those days, y’all. [chuckles]

I’m very excited to introduce our speaker, Colleen Gratzer. Colleen has spoken for us multiple times before and always gives phenomenal presentations. I got to know Colleen, actually, because I found her podcast in the very beginning through her “Creative Boost” website. She does a lot of different courses and education on accessibility. Accessibility in design, and accessibly in InDesign, and accessible PDFs, which are a great mystery to me.

She is an award-winning designer with over 25 years of experience in branding, publication design, web design, and development. And in addition to Creative Boost, she also does consulting for clients with her company, Gratzer Graphics.

So welcome, Colleen.

>> COLLEEN GRATZER: Thank you so much. And I didn’t know that that’s how you originally found me, so that’s really interesting. I didn’t know it was through my podcast.

>> AMBER: Yes. I think at one point in time, I was just looking for people, like, podcasts about accessibility because I was trying to learn more, and so I was surfing around and I subscribed to a ton. But there’s a lot out there that exists, but they’re not making new episodes anymore.

>> COLLEEN: Yes.

>> AMBER: So I feel like that’s how I first found it. But then, you know, we’ve been in a bunch of Facebook groups and all of that other stuff too.

>> COLLEEN: Right. Oh, that’s neat. OK. Awesome.

>> AMBER: So podcasting works.

>> COLLEEN: [chuckles] Yes. That’s nice to know that. Well, I’m excited to be back for, I think, my third Equalize Digital WordPress Accessibility Meetup. And as you know, I’m always excited to talk about accessibility; and apparently, I’m infamous for talking about it as well. [laughs] Infamous or famous, but one of those.

So I’m going to show you how important accessibility is for branding and your design work. And this is going to be really helpful for you if you’re any type of designer. You could be a web designer, graphic designer, logo designer, or all of the above. Because a lot of times, web designers and developers get thrust into the position of having to come up with colors for clients that have no branding when they’re building a website. So it could be any or all of the above here.

It’s also helpful if you want to deepen your design or branding expertise, and you want to charge more for your work. Or maybe you’re tired of losing out on new projects from clients. Or you want your work to reach a wider audience. Or maybe you’re tired of clients art directing you and you want to end the design wars. And maybe you want to be seen as a trusted expert by clients. Those are all huge benefits from accessibility.

So today, you are going to learn how accessibility applies to branding and design, why you need to consider accessibility as a designer, how accessibility helps you as a designer, color and contrast accessibility guidelines, how to check contrast, and then also how to check your designs for colorblindness.

Oh, am I not sharing my screen?

>> AMBER: No, not yet. I know we practiced, and I kicked you out when I started [crosstalk ].

>> COLLEEN: Look, we rehearsed this and everything, and I’ve already screwed it up.

>> AMBER: It’s all good.

>> COLLEEN: OK.

>> AMBER: I also forgot to mention that, anyone, if you want to put questions in the Q and A, I’ll watch those, and then I can pass them on to Colleen after.

>> COLLEEN: OK. Now, are you seeing the right slides?

>> AMBER: Yes, now we’re seeing “What will you learn?”

>> COLLEEN: OK, great. So you missed my nice-looking slides before that, but all right, we’ll deal. OK. [laughs]

OK, so first, I just want to really quickly dispel some common myths and objections that so many designers have when it comes to accessibility.

The first one is that so many designers think that accessibility is ugly. Accessibility does not at all mean that a color palette or a design will be ugly. And an untrained individual cannot tell if a color palette or a design is accessible just by looking at it. So you’re not limiting your creativity by incorporating accessibility, at all.

So here are some examples of some accessible websites that we’ve designed, and I don’t think that you would say that these were ugly [chuckles]. And I don’t think you’d say this one was ugly either. And then these are some accessible documents that we designed, and I don’t think that you would say these were ugly either. So they have a nice mix of colors, and there’s no limitation on the colors we’re using.

OK. And then another objection is often that accessibility means using only dark colors. And I’ve actually heard this from a lot of other designers, but I’ve also heard it from clients.

One time, actually, I had a client that sent me their color palette, but they decided that they were going to omit the lighter colors because they assumed they wouldn’t be accessible. And I didn’t even know about this until later on in the project when the client was asking about why the design was so dark. These accessible designs, like I showed earlier, they don’t use only dark colors. And these designs also don’t use only dark colors.

In fact, if you used colors, it would result in hard to read and inaccessible content. I mean, you don’t need to have a visual disability to not be able to read this. And this was so much smaller on the website than how you’re seeing it right now.

Another myth is that accessibility means limiting your choice of colors. But that’s definitely not the case. And it’s important to understand that no color is inherently inaccessible, because it’s always about how the colors are used together.

Now, a lot of people also think that accessibility is also only about warding off lawsuits. But accessibility is really about enabling everyone to read your clients’ websites, your clients’ publications, whatever you’re producing, whatever you’re designing.

OK, so what does accessibility have to do with branding and design, you’re probably wondering, which is why you’re here today. Well, when you consider color accessibility in your branding and design work, it ensures that all sighted users can read the content regardless of a visual disability.

There are about 2.2 billion people worldwide with a visual disability, so this is a big deal. And one type of visual disability is low vision, and that can be caused by macular degeneration or cataract or diabetic retinopathy or glaucoma. And those are just a few types.

Individuals with macular degeneration, they might have issues with their central vision. So this is how they might see a page that you’ve designed with the central vision hazy.

And individuals with cataract may have cloudy vision, so they might see text a little bit kind of cloudy or blurry.

Individuals that have diabetic retinopathy might see large spots on the page.

Then individuals with glaucoma may have trouble seeing peripherally on the sides. And these are just a few examples.

Now, even though accessibility applies to much more than websites, let’s take a look at this statistic from “WebAIM.” “WebAIM” assessed the accessibility of the top 1 million websites. And the most common accessibility issue was low-contrast text, and that was found on almost 84% of pages. And each home page had an average of 32 instances of low-contrast text. So this is a huge problem. This is a problem because low-contrast text is hard to read. And not just hard to read for people with a visual disability, but also for those without one.

I mean, I don’t have a visual disability and I find these hard to read. You know, you’ve got yellow text on a white background. And then we’ve got white text on a white semi transparent box over an image. And then we’ve got light green or a medium green over a light blue background. There just isn’t sufficient contrast between the text and the background.

In this example, someone with low vision may not be able to read the orange text on the white background, or the white text on the orange background.

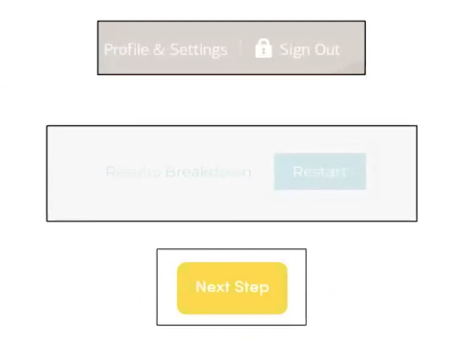

Low-contrast text is often also found on hyperlinks and buttons, making it hard for someone to not only read the content, but to take action. So we’ve got white here on, like, a brownish gray, and then we’ve got a really light blue on a gray background, and then a white on a light blue. And then, again, we’ve got white on yellow, which I see so often.

Now, when you consider color accessibility in your branding and design work, it means that all sighted users can also understand the content even if they have a disability. So not just reading it, but also understanding.

For example, people with a visual disability may not be able to see this onion in this infographic at all, right? So they might see the radish and the carrot. They may not see the onion at all because it doesn’t have sufficient contrast with the background. So they would have no idea what the 73% there is referring to.

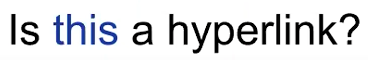

Using color alone to style hyperlink text can be confusing for sighted users because the hyperlink isn’t clearly distinguishable from the surrounding body text. And so this could be a problem for sighted users in general, and even more so for sighted users with a cognitive disability, for example.

So here we have blue text for the word “This,” but then the surrounding text is black, and there’s not sufficient contrast between that blue and black to make out that hyperlink. And no other styling is being used to show that.

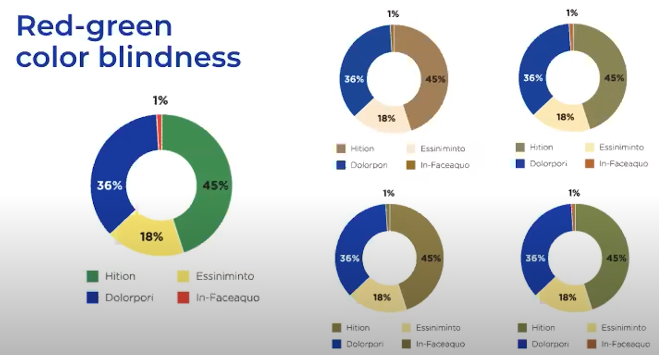

How about colorblindness? Well, colorblindness affects 8% of males and a half percent of females. And so someone with red, green color blindness could see this donut chart in one of four ways. So instead of seeing blue, red, green, and yellow, they might instead see blue, brown, pink, and tan; or blue, brown, olive green, and tan; or blue, yellow, and olive green; or maybe blue, yellow, olive green and brown. So the pie chart or the donut chart would not be understandable to them.

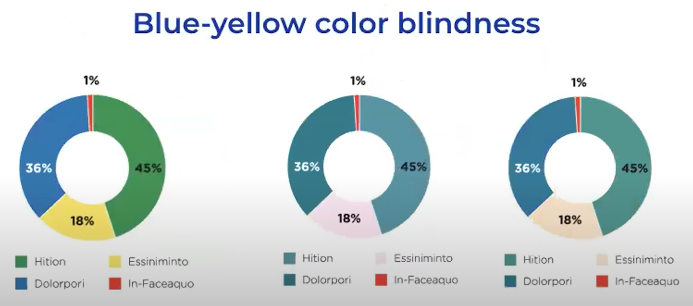

Someone with blue, yellow color blindness might see this donut chart differently, too. This one is a medium blue, red, green, and yellow, but they would see the blue as more green, and the yellow as pink or beige. And then, depending on the colors that are used, they may not be able to understand the chart at all.

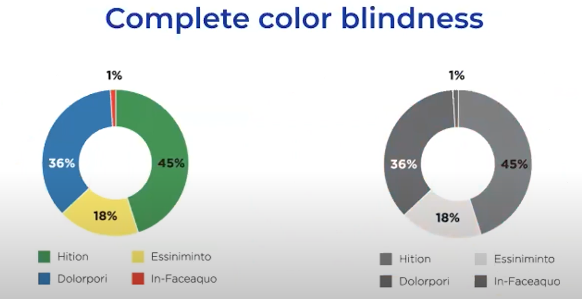

Now, in the same donut chart, someone with complete color blindness would see three dark gray shades that are really hard to distinguish from each other, plus a lighter shade. So they would not be able to understand the three darker shades and which label they correspond to in the legend.

Then we can also use color to help users with cognitive learning or neurological disability understand content as well. And some of these individuals could have autism, down syndrome, multiple sclerosis, a traumatic brain injury, ADHD dyslexia, or seizure disorder, like epilepsy.

Some color combinations have actually been shown to increase or decrease readability. And then other colors can actually trigger seizures in some people.

OK, so why do you, as a designer, need to consider accessibility? Well, a lot of designers and clients think of accessibility as an add-on, something that gets done last in the design process. But that’s actually the worst way to go about it, which I’ll get into shortly.

So the earlier on in the process that accessibility is addressed, the less it costs and the easier it is. So the branding stage is really the best place to address it. And that’s because the color palette that you create as part of a brand identity or maybe a document design or a website design, that color palette becomes the source of colors for the branding and the design work for that brand, and everything trickles down from the color palette that you create. And so when there are issues with the color palette, there can be issues in anything created from that, which might later need to be made accessible.

Now, when the color palette or a design is not accessible, it needs to be remediated, meaning it needs to be fixed to be made accessible. And it’s always more costly at that stage than when it’s considered in the process, like throughout the design process. And what happens is that this adds a lot of time to the schedule, and there might be a lot of back and forth between the accessibility specialist and the client to get things reapproved. There might be a lot of back and forth between the designer and the client, so it adds a lot of time, and that adds a lot of costs as well.

Now, when you don’t consider accessibility in your branding and design work, it can also affect the integrity of the brand. Colors in the brand color palette might need to be modified. So they might have to be lightened or they might have to be darkened, or different ones might have to be chosen, or maybe even new ones added to get things to work.

Here’s an actual example where a client came to me with an annual report that had already been designed. And the design used a very light blue and a light green from their color palette. And if I were to darken the colors to provide sufficient contrast, you can see how the light green actually ends up being like an olive green. It’s a totally different color, right?

The other thing to think about is that some accessibility specialists who take a design, like a completed file after the fact, if they’re remediating a document and they don’t have branding or design expertise, they might simply choose to darken or lighten the existing colors to provide that sufficient contrast. And so they don’t necessarily have branding or design expertise, so they’re not necessarily taking into account that color palette that you spend a lot of time creating. So if you take accessibility into account in the process, then you’ll have more control over that design.

Now, here’s another example. And this is from my own branding from one of my websites. So the two main brand colors are the light green and the gray. And the purple was supposed to be a secondary color. And I really liked this combination. I really liked the feel that they gave being used together. And the problem is that the green and the gray don’t have sufficient contrast against white or each other.

So I could have simply darkened them, right? But that would give a totally different effect than I wanted because the design in general just becomes too dark. Because we’ve got a darker green and then we’ve got a darker gray, which almost looks like the same color. So it’s, like, really blah looking. It’s not at all like the brighter design that I started with; the brighter inaccessible design that I started with.

So I ended up using the purple, again, which I wanted to be more kind of a secondary color, kind of sprinkled throughout and not so dominant. Because otherwise, I would have had to go change the design or I would have had to change the existing colors, which are pretty drastic measures to take when you already have the branding in place. So I resolved the contrast issue and made things easier to read. But you can see that the website became very heavy on the purple. So it does have a different feel to it. Of course, it is easier to read, so I’m not complaining about that, but it does have a very different feel to it, so that’s the point I’m trying to make.

Now, sometimes, it’s a matter of the design having to change, and that may be a little or a lot. And then the client is having to revisit the design process all over again. And, again, that costs time and money. And if you’re the original designer, you may not be happy that your design was modified, especially after putting so much work into it.

So here’s another actual example from a document that I remediated once. The original had orange and white text on light green, which did not have sufficient contrast. So I changed the colors to some other ones from the existing color palette, which ended up being white on blue. Totally different-looking page, right? Totally different colors.

Now, here’s another example. We got the orange and the green text on white that don’t have sufficient contrast. So instead of changing colors to other colors in the color palette or darkening them, I changed the design a bit to be able to keep the light green and add in a touch of orange where possible. So I added a purple background to get the light green to work against the purple background.

The other point I want to make about this is that when clients make only their website or a document accessible; in other words, if they just make one document accessible or maybe just the website, and they do things piecemeal, and they don’t plan on addressing it across the whole entire brand, then it can result in inconsistencies in the branding. And consistency is obviously so important for branding.

So what happens is that their marketing materials may look different and use different colors, and so their branding looks disjointed. So they might have, like, this document over here that’s been remediated, and then the website has a different look because it hasn’t been remediated yet or vice versa. And then when the branding is inconsistent, then your client can potentially lose business because some people may not immediately recognize that branding.

And so, with design and accessibility expertise, you can prevent that from happening in the first place. And of course, design is all about communication. It’s about educating someone. It’s about enticing them to buy a product. It might be, like, you want them to donate to a cause or to use a service. And your clients may assume that they don’t serve anyone with a disability, but they do.

So think about it this way. Clients can’t see who is coming to their website. They can see who comes into their offices, right? But still, some disabilities are not outwardly obvious. You can’t see if someone has dyslexia or seizure disorder or hearing loss or colorblindness, for example. And the only way that your clients might find out is if someone contacts them and says, “I can’t read the text on your website.” Or, “I can’t understand the charts in your annual report because they weren’t designed with colorblind users in mind.” Right? Or there might be another accessibility issue that they encountered.

As designers, don’t we want our work to reach the widest audience possible? Because if it doesn’t, is it as successful as it could be?

When accessibility is implemented, it enhances a brand’s reputation. People will say good things. But when accessibility is ignored, it can actually hurt the brand. People with a disability are three times as likely to avoid and twice as likely to dissuade others because of an organization’s negative diversity reputation. And this is according to the Australian Human Rights Commission.

So when clients don’t consider 20% of their audience, it comes across as, “We don’t care about being inclusive.” And you know how important Google reviews, Facebook reviews, Yelp, and other reviews can help or hurt a business, right? So accessibility is great for branding in terms of not only the visual branding but also the reputation aspect as well.

Also, when accessibility is implemented, it increases a business’s revenue. Part of that is because 71% of users with a disability will leave a website that is not accessible.

Now, of course, only part of that relates to color accessibility. But as we saw from that statistic on low-contrast text, almost 84% of web pages, at least the top 1 million ones, 84% of those have low-contrast text.

So for example, let’s say a legally blind woman goes to your client’s website and she wants to buy something from your client’s business, or maybe she wants to hire them for a service, but then she goes to the website and she finds it hard to read the text. So she’ll leave the site feeling frustrated and go to a competitor site.

Now, the other thing is that this is our chance as designers to step up, educate clients about accessibility; and not only reach more people, but help our clients get better results from our work, whether that’s branding, or designing a document, a website, or an app.

So now let’s talk about how accessibility actually helps you as a designer of any kind. When you don’t address accessibility in the design process and the client then needs to make the design accessible… A lot of times what I get from the client is that they wonder why the original designer didn’t bring this up. So I get asked this all the time when I’m remediating documents and websites. And I don’t want to throw other designers under the bus, right? I just want to help them be aware of this and learn how to do it. So when you consider accessibility in the process, it actually enhances your reputation.

Accessibility also gives you a competitive edge over 99% of other designers who aren’t thinking about this at all. And then a lot of the ones that do know about it aren’t doing it correctly. But accessibility is only becoming a bigger and bigger issue worldwide. And in many countries, there are accessibility laws and they’ve been around for decades. But even when clients don’t have a legal requirement, clients are taking notice and they’re asking for it more and more.

Let me tell you, there are a gazillion designers out there, especially web designers. And if you’re not niched, it is especially hard to stand out. So accessibility can help you stand out and actually win more work.

Now, accessibility also enhances your branding and design expertise, like with the information I shared earlier. It’s like a deeper understanding of branding and design. It also makes you a more confident designer. It makes it so much easier to explain your design decisions when you’re talking to the client, and you can totally win those design wars. [chuckles] And then design decisions aren’t based on, “Well, Bob likes blue, so we’re going to go with blue.” [chuckles] And you can easily charge more because your work has even more value because it reaches a wider audience.

There are several opportunities with branding and accessibility that you can make money from. There’s a huge need in this space, particularly for designers. But like I said too, you can win more work, but you win more work more easily. That’s been the case for me. I mean, it’s been a complete game-changer for me.

One of my web accessibility course students, right after starting the course just by talking about it, he won five jobs simply by talking about accessibility because nobody else was bringing that up to the client. [chuckles] But you’ll also get more respect and be treated like an expert.

As I said, clients will stop art directing, they will stop overriding your design decisions. You’ll end the design wars, and it’s really awesome when that happens.

Accessibility also means that your work will get better results, and that’s because it reaches more people. And that could be 20% more people, or it could potentially be even more than that, especially if you have a client who serves people with particular disabilities. But when your work gets better results, it means clients will be happy with your work, and then they will have a better reputation and increased revenue. And that means they will come back to you again and again. And your work will make a difference because it’s being inclusive of 20% or more people rather than alienating someone.

I’ve experienced all of these points with accessibility. I mean, I’ve had my own business since 2003, and I have done every type of design work out there. I have done publication design, website design, website code, logo design, email design; you name it, I have done it. But of all the things that I’ve done to help my business, the number one way that I helped my business was with accessibility. And it was so strange because I got into it by accident in 2016, and I didn’t expect it was going to completely change things.

As I mentioned, I mean, I eliminated 99% of my competition. I started winning almost every project instead of wondering why new clients weren’t hiring me and I was only getting referral work most of the time. And then work started coming to me from all over the place. And I started charging more, and I became so much more confident.

OK, so there are several accessibility guidelines that we can utilize to help us make sure that the colors that we use in our designs are accessible, how we’re using those colors. So the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines called WCAG, these guidelines tell us how to be compliant.

Now, there are many guidelines, but I’m only going to cover the ones that deal with color choice. Because there is so much more that goes into making a document or a website accessible. There are more technical things to do, so I’m just going to cover color.

Now, if you’re not familiar with the WCAG guidelines, there are three levels of conformance. There are A, AA, and AAA. And so they range from the bare minimum to stricter. So A is the bare minimum, AA is the default, and then AAA is actually stricter, but it’s also extremely rare of a request to get that. And most accessibility laws call for AA conformance.

Now, the first one that has to do with color is WCAG 1.4.1 use of color. And this is a level A guideline, which, again, is a very basic level. So this guideline tells us that color cannot be used as the only visual means of conveying information, indicating an action, prompting a response, or distinguishing a visual element.

Remember the donut chart that I showed earlier? Well, if we use color alone as opposed to contrast or some other styling to convey that information, then it can make it difficult or impossible for someone with colorblindness or a low vision to understand the information. And if color alone is only being able to distinguish hyperlinks from surrounding body text, then individuals with certain visual disabilities, even sighted users without a visual disability may not be able to tell that is the hyperlink, that the word “This” is the hyperlink, because the blue for “This” does not contrast enough with the black text in the sentence.

Now, WCAG 1.4.3 is contrast minimum, and this is level AA, so it’s in the middle level. And it says that text and images of text that are normal size must have a minimum contrast ratio of four and a half to one against their backgrounds. OK, what the heck does that mean? Let’s break this down.

So large text has a lesser requirement, and that’s a minimum of three to one against the background. So text is considered large when it’s at least 14 points and bold or 18.66 pixels and bold, or at least 18 points or 24 pixels in any width.

So in a design, normal-sized text is likely to be body text, sidebar text, running headers and footers, captions, footnotes, graph text hyperlinks, table text, form fields, and maybe buttons. But large text might be headings, pull quotes, maybe infographic text, maybe table headers, and maybe buttons.

Now, on websites, normal text might be the post metadata, the body text, and the navigation text. And then the large text might be certain headings, and then possibly button text and maybe block quote text.

Now, contrast minimum could also apply to text that is part of an icon that is conveying information. So in this particular example, we have icons that say SVG, PNG, and JPEG which are image file formats. So if somebody cannot read that text, they cannot tell what that icon is conveying. But this could also apply to text in a data graphic, like the donut chart.

Now, there is another contrast guideline that is stricter and that is 1.4.6 contrast-enhanced. So the other one was contrast minimum, level AA. This is contrast-enhanced, level AAA. So it’s a little bit stricter. But again, AAA is a really rare request. But in this case, the normal text would need to be at least a seven-to-one ratio instead of four and a half to one. And then large text would need to be four and a half to one or greater instead of three to one.

I actually have a client who follows AA conformance, but then they actually request to follow AAA conformance for all of their text. Nothing else; just for their text.

Now, there’s also a contrast guideline for non-text elements, which WCAG refers to as graphical objects and user interface components. And this is WCAG 1.4.11 non-text contrast. And so these elements need to have at least a three-to-one ratio of contrast against adjacent colors.

So an example of this would be parts of a graph, such as the lines on the graph representing data, the squares in the legend conveying information about that data. And the colors used for the lines and in the legend need to have sufficient contrast between them and those lines and the background so that individuals with visual disabilities will be able to see the lines and then also tell which one is which to understand that data. And then giving the gray lines that have the range for the numbers, giving those sufficient contrast helps people with low vision more easily tell where the data points are on the graph.

Non-text contrast could also apply to social media icons, and it also applies to form elements. So form fields, for example. And that’s so that somebody can see the fields and also know where information goes. And non-text contrast applies to icons used in place of buttons, such as a magnifying glass icon used in place of a submit button for a search field.

If they can’t see that icon, then they can’t tell that there’s, like, a button there for “submit” to submit the search query.

Now, because this is a branding and design talk and I went over how important accessibility is for those already, you might be surprised to find out that there is actually no contrast requirement for logos. But I hope now that you can understand why you would want to consider that anyway even though it’s not a requirement. And decorative elements that don’t convey any meaning, also don’t have a contrast requirement. And these could be decorative borders, decorative icons, or potentially quotation marks that are used in pull quotes.

So you don’t have to remember all of the guidelines because, fortunately, we have all kinds of checkers that will help us.

So now that you know more about color and accessibility, how can you find out if the colors that you choose are accessible? Well, checking contrast is just one thing to consider with colors, and you can easily get started by using a contrast checker to check your color combinations.

One contrast checker is the TPGI Colour Contrast Analyser, and that is with the British spelling. And this is a downloadable program and it samples color from anywhere on your screen, so it’s really convenient.

Now, I said a moment ago that contrast guidelines don’t apply to logos, and they don’t. But I used my logo as an example, because you may recall when I was talking about my brand colors and the accessibility issues they presented with the contrast on my website.

So again, the guidelines are only that: the guidelines. So if you’re aware of what can happen with your choice of colors, then you can prevent these kinds of issues.

So here, I’m using the TPGI Colour Contrast Analyser, and you can see that you can sample on the screen, but then you can also adjust the hue, saturation, and lightness of the colors to try to find a combination that does pass for large text or for regular text, or for AA or for AAA. And it gives you the reading right there to tell you what it passes for.

Again, if it passes for large text or normal text, and for AA or AAA, or for the non-text contrast guideline.

Now, it also allows you to input hexadecimal codes, which are the six-digit values, and also RGB and HSL values. And you can get those from a design program.

So if you use InDesign, for example, you can get the color values from the swatches palette and insert them into the Colour Contrast Analyser. So you don’t have to use it as a sampler; you can also use it to input the codes. And you can also get these values from Illustrator, Photoshop, Word, PowerPoint, Canva, and other programs.

So here’s how you would do that in InDesign. You would just double click the color in the swatches palette and then change it to RGB mode if it’s not already in RGB mode. And you don’t have to keep it in that, just temporarily do it. And then you just copy that hexadecimal code, the six-digit code at the bottom, and you can just paste that into the checker.

Here’s how you would do that in Illustrator. You would just click on the color palette and then switch the flyout menu to RGB mode, just like you would in InDesign. And then you get the hexadecimal code there. And since you couldn’t see the flyout menu in the video, here’s how that would look. Just select RGB.

Here’s how you would do that in Photoshop. You just select the color swatch, and then the hexadecimal code appears at the bottom of the dialog window that opens up there. And then there is Adobe Color, “color.adobe.com.”

Now, on the website, you would just go and select “Accessibility Tools,” And then you can select which WCAG level that you need to abide by, but it’s usually 2.1 AA or 2.0 AA, and then you just paste or type in the hexadecimal codes for the foreground and background colors. And then it gives you the contrast ratio for that combination, along with some recommendations on the right side.

You can also lighten or darken one of the colors to increase the contrast and check for a combination that meets the requirement. I mean, sometimes it can just be a little tweak and then you can get it to meet the contrast requirement.

You can also do minor checks for colorblindness. Now, here are two that are really easy to do when you’re designing something in Illustrator or Photoshop. You can check for a couple of types of color blindness in Illustrator. Now, there are multiple types of colorblindness, but you can check for a couple of them in Illustrator, the two of the most common types. So you just go to “View” and then you go to “Proof setup” and then “Colorblindness protanopia.” Or you can go back and go to “Colorblindness deuteranopia.” So this is especially handy if you’re designing infographics, so you can see if someone would be able to differentiate, in this case, different fruits from each other.

The shape is differentiating them, not the color. But in some cases, you might be using color, so you’d have to adjust that. And you can do the same thing in Photoshop. Just, again, go to “View,” and then “Proof setup,” and then choose “Colorblindness protanopia” or “Colorblindness deuteranopia.”

OK, so there is so much more to learn about accessibility, of course. And in this presentation, I only covered some of the visual aspects that had to do with color. There are technical aspects that also apply, like when you lay out a document or you build a website and there’s things that happen in the setup that account for the technical part of accessibility.

If you’re interested in learning more about accessibility and color, then you can download my free color accessibility toolkit, which includes the guidelines, but also many, many tools that you can use for checking the colors in your color palettes, in your data graphics, and in your documents and websites. If you’re interested in that, you could go to “creative-boost.com/edmeetup.” E-D as in Equalize Digital Meetup. And you’ll also get some additional accessibility tips on color and other things as well.

So I am happy to answer any questions about color and accessibility and branding.

>> AMBER: Yes. let me figure out how to have myself back in here. We did get some questions. I saw a couple from the chat. I did mark those down, so I’ll circle back to those. I’m going to start with what’s in the Q and A. So if you have questions, please feel free to put them in the Q and A.

The first one that we got, someone said, “When I deal with clients and sharing my screen on Zoom, very often, about 90% to 95% of the time, I am inverted and they can’t see that. Do you have any suggestions on what I can do other than being very descriptive with my color terms and definitions?” They said they’ve reached out to Zoom, and they haven’t heard from them.

So I’m guessing that means, like, the colors are inverted. And I’m not sure if that means that they’ve set their operating system preferences to do inverted colors for accessibility reasons, and they’re trying to figure out how to describe what they would be. I don’t know if you have any thoughts about this. And also –

>> COLLEEN: I’m not sure…

>> AMBER: – For the person who asked, feel free to add extra context if you need to.

>> COLLEEN: Yes, please add some extra information.

>> AMBER: OK. Yes. So maybe we’ll circle back to that one because I also am not 100% sure. So feel free if you have extra context. I’m not certain. Like, how I interpreted it was maybe that they were… Like, if you have an inverted monitor because that’s what you see best, but you’re creating things for clients, like, how would you design it? And my thought would be you would want to export it and just send them the file because then they would see it on their monitor, not inverted, right? Rather than doing a screen share.

>> COLLEEN: Yes. If there’s something that they’re not seeing because it’s a screen share, then, yes, I think a screenshot would be the way to go, so they can see the same thing that you’re seeing.

>> AMBER: Yes, maybe. Let us know if that didn’t answer the question.

Constantino [phonetic] was asking, “How do we make inverted contrast and colors a bigger priority?” Says, “Some of the bluest chips I deal with still don’t understand that it’s not dark mode and that it’s completely different.” And he said, “Bangs head on desk.” [chuckles]

>> COLLEEN: [chuckles] Oh, no.

>> AMBER: So do you have any thoughts about convincing people on coming up with inverted color palettes?

>> COLLEEN: That’s very interesting. So I haven’t thought about that before, but… So you could try… I don’t know if the Funkify browser extension maybe does… Like, because that’s a simulator for different visual and motor disabilities. I don’t know if they have something in there, but… Yes.

>> AMBER: Yes. So Nick Croft’s presentation, he was talking about doing, like, the CSS behind inverted colors. And I’m trying to think… He works at Reactive, which is a WordPress agency. And I think based on what he said, my understanding, is they’re just doing it. So I guess you probably have to have clients at a certain budget range. I don’t know if they do it on all of the projects that they’re working on. I don’t know.

If you have a client that’s doing a full accessibility test, then you should be checking for colorblindness and, like, good contrast during inverted. Like, if someone is viewing on an inverted or they have their operating system set to that. So I would think that those are the clients that would be easy to convince that they need to make sure they have good inverted color contrast. But I don’t know if I have tips for convincing them.

>> COLLEEN: Yes.

>> AMBER: Probably the best thing would be to show them what it looks like and say, “When I have an inverted setting, it’s not readable.” And maybe if they see a screenshot of it, then that would convince them that they should spend time thinking about the colors.

>> COLLEEN: And then also who are their audiences too? I mean, if they’re serving an audience with visual disabilities, that might be an easier sell than if it’s not.

>> AMBER: Yes. Do you know any good resources on… I don’t, so I might be throwing you, like, maybe there isn’t one, but maybe you know of one. Do you know if anybody has statistics on how many people have their operating system set to either inverted or, like, dark mode preference?

>> COLLEEN: Oh.

>> AMBER: Have you ever seen that?

>> COLLEEN: I think I’ve seen stats somewhere on high contrast mode.

>> AMBER: OK. Do you know, vaguely, what it is, or are you [inaudible]?

>> COLLEEN: I don’t remember. Let me see if I can just look real quick on my computer to see if I have that, but I don’t recall offhand where it was. But let me see if I can find it.

>> AMBER: Yes, maybe you can pull that up. I feel like having the numbers, that’s what Samuel [phonetic] in the chat said, maybe stating how many folks have visual issues. 2.2 billion.

I thought it was really great in your talk when you were showing the examples of different types of cataracts or glaucoma or things like that and how different people see. Because I think sometimes, clients or website owners, let’s call them, or, like, marketing people, they just think it’s either, like, normal vision or blind. And they think, “Oh, there’s not very many blind people.” [chuckles]

>> COLLEEN: Right.

>> AMBER: But they forget there’s this whole spectrum of other people that it applies to. And so giving numbers, I think, could be really helpful.

Feel free, you guys. If anyone else knows these stats, throw them in the chat and I’ll shout them out.

Let’s see. Adrian [phonetic] did ask, “Is inverted colors the same as high contrast?” Do you want to answer that one?

>> COLLEEN: I don’t know if that’s considered the same thing.

>> AMBER: I don’t think it is. I think inverted colors, in my understanding, would be closer to doing more like a dark mode versus light mode.

>> COLLEEN: Yes.

>> AMBER: I think a lot of times, high contrast is frequently inverted, but I don’t think it has to be.

>> COLLEEN: Yes.

>> AMBER: Let’s see. Donald [phonetic] added in. He said, “When I used to work on aircraft, color blindness was a disqualifier. All fluid and air tubular lines had tape wrapped around them as an identifier. First was a white background strip with an S-specific symbol for the use and in the content of the line. And next was a two-color band that was also for a specific line use. Finally, the content or use of the line was written across the tape.”

He said, “Couldn’t symbols be used with pie charts or other charts to identify each component purpose for colorblind individuals?”

>> COLLEEN: Absolutely. Yes. Because then you’re not relying on color to convey that information. So if you are using color and it has sufficient contrast, then you’re no longer relying on color. But you don’t have to rely on contrast either. You can use different shapes as long as those shapes have sufficient contrast against whatever background they’re on so somebody could make out the shape.

>> AMBER: Yes. So I think it’s 1.4.1 use of color, which is a single A, and it specifies that you shouldn’t use color alone to indicate important things.

So, like some of the charts, one of the things I thought I had on the line graph you had with the two, the red and the blue lines, was another way to distinguish that besides having good color contrast is one of them could have been like a dashed line, or a line with little dots on it or something. And the other one could have just been a solid line.

>> COLLEEN: Right. Or sometimes what you see… I think sometimes in some PowerPoint things, I guess it is, is that you might have a line that has, like, circles on each data point, and then the other line in the graph has triangles or squares on each line of its data points. But that can get tricky if the lines still don’t have sufficient contrast against each other if they’re overlapping because then it’s hard to make out where which one is going. Because it might be hard to tell which one is which at that point if they overlap. So it can get tricky.

>> AMBER: Yes. So Anna [phonetic] asked… This is sort of on the other side of things. If a website has 000 text, so straight black on FFF, straight white background, should she mention to them that that’s too much contrast?

>> COLLEEN: So it’s not a failure for having that contrast, but that’s the highest contrast. So that can affect people with Irlen syndrome, who might see the text on the page as moving or wavy, or blurry. So you could just easily, very slightly, narrow the contrast by either changing the white background to something very slightly off-white, or making the black almost black, but not the darkest black.

>> AMBER: Yes. I think we try not to go super high. When you were talking about contrast, like, we’ve had some success with getting a lot of our clients to AAA color contrast, not necessarily AAA everything else.

>> COLLEEN: Right, right. [chuckles].

>> AMBER: That’s a hard job. But I feel like we’ve had a decent run at that. But, yes, then we go the other direction, which is it shouldn’t necessarily be all white on black or black on white.

>> COLLEEN: Right.

>> AMBER: So earlier on… [inaudible] the chat. Jeff [phonetic] in the chat had said, “What happens when the client already has the logo and a brand, but the palette is not accessible?”

Jeff has a client that uses pastel Easter egg colors, which are awful. They’re hard-headed, and they have stuck with those colors.

So do you have any recommendations for making pastel Easter egg colors work in a design?

>> COLLEEN: Yes. So there are a few things. I mean, you could use maybe dark gray or black text on those colors. [crosstalk ].

>> AMBER: Obviously, inversed, right? Like, have a dark gray background with those colors for the text?

>> COLLEEN: Well, I was thinking more, like, since those colors won’t work against white, probably, from what it sounds like, that you could kind of use it as a design element, where maybe you have a heading that seems like the heading… Because normally your text is going to be like the dark gray or the black. So you want to use the colors to give more variety on the page.

So maybe what you could do since you can’t use the Easter egg blue or the Easter egg green or whatever the color is as the heading against the white background, then you could make the heading like a design element, and, like give it a background, maybe they’re of, like, gray or black or something. Something that’s still neutral and works with the color palette doesn’t change up the branding too much, but it provides that background to give that sufficient contrast.

So you still get your light blue heading or your light green heading or whatever it is, but you’re just adding the color behind it. But you can use it as a design element.

There are so many things you can do with CSS now. You could have it be like a funky shape in the background of it just to get that contrast, you know. So [inaudible].

>> AMBER: Yes, I’ve seen things where it’s almost like they make it look like the heading has been highlighted…

>> COLLEEN: Yes. I was just thinking that. Yes, yes.

>> AMBER: But having just like a bit of an offset or something?

>> COLLEEN: Yes.

>> AMBER: Yes. I think Alicia [phonetic] mentioned in the chat you could use that color for all your decorative icons.

>> COLLEEN: Yes, exactly. I mean, it’s a lot if the only colors you’re given are, like, pastel. But, yes, if you have at least a color that’s like a non-gray or a non-black color that you can use somewhere to qualify as large text, then you can use those other colors as decorative elements so the page isn’t, like, too heavy on one color.

>> AMBER: Yes. I mean, I feel like whenever we get clients like that, we tend to be, like, “Hey, maybe we can have a dark background at the top so that you can have your text in these bright colors that you want or pastel colors that you want.” So we end up with either a dark gray or a dark blue or something like that that’s, like, a background, and then the body might end up being in white. But you’ve got, like, a hero or a top section of the page that is a darker when you first land on it, which is kind of modern, I feel like. I see a lot of websites where they have really dark tops.

>> COLLEEN: Yes. But in some cases, if you add black to the color palette and you’re using it decoratively, it might end up being too much. But it could also really work with other color palettes, too. So it really depends on the client and their branding.

>> AMBER: Yes. Samuel is doing research for us. Thank you, Samuel. Samuel sent stats about high contrast mode and shared a link to Smashing Magazine, an article in 2022. It says, “About 4% of active devices use Windows high contrast mode. And thanks to WebAIM’s survey of users with low vision, we can estimate that around 30% of users with low vision use Windows high contrast mode.” So 4% of all devices. That’s actually really large, I think.

So there’s your answer. And hopefully, that’s a helpful stat for selling clients on thinking about high contrast in design.

>> COLLEEN: I have seen that page before. [chuckles]

>> AMBER: That article on Smashing Magazine?

>> COLLEEN: I’ve seen that before. Yes.

>> AMBER: I don’t know if I read that one before. I’m going to have to go read it.

Glenn [phonetic] says, “Just for fun, I tried a bunch of pastel colors with white, and they were all under two to one. So even large text, it wouldn’t work.”

Yes. I think you’d have to have a dark background.

>> COLLEEN: I mean, the other thing you could do if it’s really short and large text is, you could do an outline. You don’t want to do that [crosstalk ]

>> AMBER: Oh, yes. As long as you have a one-pixel outline. A one-pixel border. I think a drop shadow counts too, as long as it goes all the way around. And then it would technically pass. Of course, then it’s like the ’90s of web design [chuckles], drop shadows on everything. As long as you don’t also add bevels on your button.

>> COLLEEN: Right. Don’t be adding bevels or gradations. [chuckles]

>> AMBER: Yes. I think the other thing that I liked in your talk when you were talking about, like, putting the dark behind, was you used a dark purple.

>> COLLEEN: Yes.

>> AMBER: And so I think a lot of people jump to, “Oh, if I have pastel colors, I have to put a black or a dark gray behind it, and I don’t like that.” Well, if you have a pastel blue, you could maybe use a very dark navy or you could use a very dark green. Or like you did, like you used a purple behind it and it gave it sufficient context. And it wasn’t necessarily like you had to put black behind everything.

>> COLLEEN: Right. And that purple also kept things warm and more vibrant looking. So yes.

>> AMBER: Yes. Maybe I’ve heard you say this… No, it’s totally… I think I’ve seen you say this in Facebook groups, like, there are no inaccessible colors? You’ve said that before, right?

>> COLLEEN: Yes.

>> AMBER: OK.

>> COLLEEN: And I said that today. Yes.

>> AMBER: Yes. It’s just, like, how you use them.

>> COLLEEN: Exactly. There are so many designers that say, “I can’t use yellow because it’s not accessible.” “I can’t use light green or orange because it’s not accessible.” It’s accessible. It’s just not accessible against white. [chuckles]

When I came up with my color palette, that was long before I got into accessibility… So when I got into accessibility and I was working through that stuff, I was like, “Oh, this is going to be a problem. [laughs] I have a lot of contrast issues I got to fix.”

>> AMBER: Yes. I felt you on that green and gray because before we did our rebrand, we were all green and gray. [laughs]

>> COLLEEN: Before that, I had, like, a cyan and gray. I think I got worse. I think that was a little bit darker than my light green. Yes.

>> AMBER: Yes. There are multiple people that are saying… Yes, Alicia says yellow has been working for Amazon. Adrian says they have yellow. Yes, we have yellow. You can use yellow. You just got to not use it with white.

>> COLLEEN: Right.

>> AMBER: Another comment that I had written down that I thought… And I don’t know if you saw this, because it was while you were talking way back in… When you were talking about getting started or, like, kind of doing it from the beginning.

Adrian had said that, “For a home-building client, I explained how they wanted to include accessibility at the beginning by comparing it to an accessible bathroom after the home is built versus in the planning stages, and that created sort of an AHA moment for the client.”

So I don’t know if you have any similar analogies or things that you use to communicate with clients that help them understand why it’s better to think about it earlier in the branding process.

>> COLLEEN: Yes, I mean, I’ll tell them about the same reasons that I mentioned today about cost and remediation. You don’t want to have to go back and redo things.

One of the other things that I say, if I have to bring it up, about how accessibility is useful even to people that don’t have a disability, I like to bring up the story of like… So when I had an apartment in my twenties… I had an apartment and they only had, like, one unit left available for rent. And so they gave it to me, but it was a handicap-accessible unit, and I didn’t need that. But that’s what I rented and I loved it. I loved it because it had much wider doorways everywhere because it had to accommodate a wheelchair. So I had extra-wide doorways to my bathroom, to my bedroom, everywhere. And it was the most awesome thing ever. Especially because I’m super clumsy, I have really broad shoulders, I bump myself constantly on normal-width doorways. So for me, that was great, right?

It’s, like, that’s not something that you might think about or seek out unless you need it, but it was just a tremendous benefit to have. It was like, “Oh, this is a cool feature for me.” But it’s not a feature for somebody that needs it. So it was a really cool thing to have.

So I like to bring that up too to help them understand how accessibility really isn’t just about only serving people with a disability; it’s also about how it helps everybody, even if they don’t need to have it.

>> AMBER: Yes. Yes. I mean, the color stuff, I feel like it bothers me all the time. I mean, I wear contacts, but, like, once I have them in, I have typical vision. But even then, like, color contrast I have trouble with.

I’d mentioned in the chat, like, I get emails from my kids’ school all the time that I’m, like, “I can’t even read this.” I have to zoom in… Because I do it all on my phone, first of all. Like, I’m checking my personal email on my phone, on the couch, like, I’m not sitting at my computer. That’s work. [chuckles]

So I’m, like, zooming in, and I’m, like, having to open… They put, like, images in their email because they try and get fancy in Canva.

>> COLLEEN: Yes.

>> AMBER: I feel a little bad, because I’m, like, I know these teachers are working hard. Putting in extra effort, like designing in Canva. But I’m a little bit, like, “I wish this Canva didn’t exist sometimes, because I would just rather get a plain text email from them with the information in, like, dark gray or black on white that’s mobile responsive and not this thing.”

>> COLLEEN: I mean, I can’t get over how many times I see… And I’ve been guilty of it in the past, OK, a long time ago. But, like, white text on a yellow background or vice versa. And now when I see product packaging… I see product packaging like that all the time and that drives me crazy.

I even saw a product package the other day that had white text on light blue, like, a cloud blue, super light blue, and that was on top of, like, a semi-transparent packaging. I’m like, “Who can read that?” [chuckles] You know? It’s like…

>> AMBER: I cannot remember… I could be wrong, but I think it was on the WP Build podcast this week in WordPress, there was an episode where they were talking about WordPress Accessibility Day right after we opened our speakers, which, PSA, apply to speak. Everyone, Colleen, go apply to speak. Everyone go apply to speak. We pay $300 because we’re not part of the WordPress Foundation so we shouldn’t pick speakers.

Anyway, they were talking about it, and I’m pretty sure it was on there. I could be wrong and maybe I saw it somewhere else. But I’m pretty sure one person on that, which they’re all what we would think of as typically sighted people, some of them are a little older, said that they have so much trouble with product packaging these days that they actually have to get out their phone, take a picture of the product so that they can then zoom in on their phone because the type is so small, and then sometimes it also is contrast. And that’s the only way they can read labels on products.

>> COLLEEN: I’m having a horrible time reading fine print on just ingredients… Not even fine print, just ingredients, and stuff in directions, like, on, my dog supplements and stuff. I’m, like, “I can’t read this stuff anymore.”

[laughter]

“I can’t read this anymore. My God. My vision is going.” I’m, like, I’m going to have to start taking pictures because it’s… I’m, like, either type is getting smaller, or my vision is going. I’m not sure which it is.

>> AMBER: Oh, Alicia says, “You don’t even have to take the picture. You can just use the camera on your phone and zoom in.” And then you can use it, like, as a magnifying glass, I guess [chuckles]. That is definitely handy now that we have phones in our pockets.

Well, I don’t know if anyone has any other questions. So can you just give everyone a quick, like, where they can find you if they want to follow up or if they have additional questions?

>> COLLEEN: Sure. So my consulting business is Gratzer Graphics. That’s gratzergraphics.com. That’s G as in George, R-A, T as in Tom, Z as in zebra, (E-R) graphics.com. And then my course business and my podcast can be found “creative-boost.com.” And then the free guide that I’ve got for you guys is “creative-boost.com/edmeetup.”

You can email me at Colleen@creative-boost.com.

>> AMBER: Awesome. And are you on any of the social media these days?

>> COLLEEN: I’m on most of them. I’m not always on them, like, all the time. [chuckles] But I’m on Instagram. I have a Facebook group called “Design Domination.”” And then I’m on LinkedIn as “Colleen Gratzer.” Twitter, but I’m not on there too much. But, yes, I’m on most of the things. [laughs] Not always [inaudible].

>> AMBER: Oh, and we got a request. “Can you throw your link to your podcast in the chat?”

>> COLLEEN: Oh, sure.

>> AMBER: They’re all posts on there, right? So you can also read the full text of them on the “Creative Boost” website?

>> COLLEEN: Yes. When you go to the website, it’s like a blog article, and then there’s the audio player for the podcast. Also, I have videos on YouTube. I didn’t originally start my podcast five years ago doing videos. I’ve been taking baby steps to get there. And now I do live talk, so I graduated. [laughs]

So I have the audio player on there, but I can also be found on YouTube. But if you look at older episodes, they’ll just be like a static image and audio, and that’s it. So there won’t be any action going on there. Yes. So you can read them on the website or you could listen to them. Either way. Yes.

Oh, and I saw that Alicia mentioned something about patterns. That’s also a great way to differentiate things too instead of using color.

>> AMBER: Yes. Well, thank you. This was fantastic. Lots of people were saying… I don’t know if you were able to watch the chat while we were [crosstalk ].

>> COLLEEN: I know. It was totally [inaudible], when I was… No, I didn’t see it.

>> AMBER: Yes. So a lot of people said it’s fantastic. Also, Billius [phonetic] thinks you sound like Jennifer Aniston.

>> COLLEEN: Who thinks I sound like Jennifer Aniston?

>> AMBER: [laughs] Billius, one of our attendees, said that.

>> COLLEEN: Oh.

>> AMBER: So you have a famous voice. [chuckles]

>> COLLEEN: [laughs] Well, you know, I was already told by Constantino [phonetic] earlier that I was famous. Maybe he was confusing me with Jennifer Aniston. You never know.

[laughter]

>> AMBER: Your doppelganger. So.

All right, well, thank you very much.

>> COLLEEN: Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity.

>> AMBER: And thank you, everyone, for attending.

If you’re able, come back on Thursday at 04:00 pm US Central Time for a panel discussion for Global Accessibility Awareness Day. And even if you can’t come to our event, there are a ton of events that day. If you just go to “accessibility.day,” that’s the website. I know it sounds weird, but “accessibility.day,” and you can get information about the other events. Share it because that’s the day to help everyone who might not have thought about document or website accessibility to know that it is a thing and that they should be thinking about it.

So please help promote and spread the word on social media, or with your business contacts on that day, and we’ll see you back there then.

>> COLLEEN: Thanks very much. Have a good night.

Links Mentioned

- Gratzer Graphics

- Creative Boost

- Progress Over Perfection: The Better Way for Communication and Accessibility Advocacy

- TPGi’s Colour Contrast Analyser

- Adobe Color

- Color Accessibility Toolkit on Creative Boost

- Accessibility Inspector on Firefox

- Using High Contrast Themes in Windows 10

- The Guide To Windows High Contrast Mode

- Design Domination Podcast – Creative Boost Podcast

About the Meetup

Learn more about WordPress Accessibility Meetup.

Article continued below.

Stay on top of web accessibility news and best practices.

Join our email list to get notified of changes to website accessibility laws, WordPress accessibility resources, and accessibility webinar invitations in your inbox.

Summarized Session Information

In this session, Colleen Gratzer addresses common myths and misconceptions about accessibility in design, emphasizing its importance and benefits. She highlights that incorporating accessibility into design does not compromise aesthetics but rather enhances the inclusivity and effectiveness of the work.

Colleen debunks several myths, such as the notion that accessibility makes designs ugly, requires only dark colors, and limits the choice of colors. She explains that accessible designs can be visually appealing and creative, using a variety of colors as long as they meet contrast and readability standards.

The session underscores the necessity of considering accessibility beyond legal compliance. Colleen emphasizes that accessibility ensures inclusivity for all users, including those with visual, cognitive, learning, and neurological disabilities. By integrating accessibility from the outset, designers can create more readable and engaging content for everyone, thus maintaining brand integrity and consistency.

Colleen delves into the impact of accessibility on design and branding, discussing how it affects users with visual disabilities, such as color blindness and low vision, and those with cognitive and neurological impairments. She highlights the importance of thoughtful color contrast and balance to enhance readability and comprehension for all users. The session also covers addressing accessibility during the branding stage to avoid costly and time-consuming adjustments later.

The session provides an overview of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) on color use and contrast. Gratzer explains the different conformance levels (A, AA, and AAA) and their significance in ensuring that designs are accessible. She discusses specific guidelines, such as using color not being the sole means of conveying information and the required contrast ratios for text and non-text elements.

Additionally, Colleen introduces tools like the TPGI Colour Contrast Analyser to help designers check and ensure that their color choices meet accessibility standards. She also demonstrates methods for testing color blindness in design software like Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop, enabling designers to create more inclusive infographics and visual content.

This session provides designers with practical knowledge and tools to create accessible, visually appealing, and effective designs. By emphasizing accessibility, designers can enhance their reputation, gain a competitive edge, and contribute to a more inclusive and welcoming digital environment.

Session Outline

- Common myths

- How accessibility applies to design and branding

- Why you need to consider accessibility

- How accessibility helps you

- Color accessibility guidelines

- How to check contrast

- How to test for color blindness

- Learn more about accessibility

Common myths

“Accessibility is ugly.”

Many designers mistakenly believe that accessibility compromises a design’s aesthetics. However, incorporating accessibility into your work does not mean your color palette or overall design will be unattractive. In fact, an untrained eye cannot easily distinguish whether a color palette or design is accessible just by looking at it. Embracing accessibility does not limit your creativity in any way.

To illustrate this point, Colleen provided examples of accessible websites her team has designed, none of which could be described as ugly.

Similarly, she showcased accessible documents they have created, all featuring vibrant color mixes.

These examples clearly demonstrate that accessibility can coexist with visually appealing design, dispelling the myth that accessible designs are inherently unattractive.

“Accessibility means using only dark colors.”

A common misconception is that accessibility requires the exclusive use of dark colors. This belief is prevalent among both designers and clients. Colleen shared an experience where a client provided a color palette but omitted lighter colors, assuming they wouldn’t be accessible. The issue only came to light later in the project when the client questioned why the design appeared so dark.

Contrary to this myth, accessible designs rely not solely on dark colors. As demonstrated by earlier examples, these designs incorporate a variety of colors. Relying only on dark colors can actually lead to content that is hard to read and thus inaccessible.

Colleen emphasized that readability issues are not confined to those with visual disabilities; poorly chosen colors can affect everyone’s ability to read content. This reinforces that accessibility is about thoughtful color contrast and balance, not just the use of dark colors.

“Accessibility limits my choice of colors.”

Another prevalent myth is that accessibility imposes strict limitations on your choice of colors. This is not true. No color is inherently inaccessible. The key to accessibility lies in how colors are used together. The contrast and combination of colors determine accessibility, not the individual colors themselves. Therefore, designers have a wide range of colors at their disposal, and with thoughtful use, they can create accessible and visually appealing designs without feeling restricted.

Accessibility is not just about warding off lawsuits

Many people mistakenly believe that accessibility is solely about avoiding lawsuits. However, accessibility’s true purpose goes far beyond legal compliance. It is fundamentally about ensuring that everyone, regardless of their abilities, can access and engage with your clients’ websites, publications, or any other designed content.

Accessibility is about inclusivity and equal opportunities for all users to interact with and benefit from your information and services.

How accessibility applies to design and branding

Visual disabilities

Understanding how accessibility impacts branding and design is crucial, particularly when considering color accessibility. By incorporating accessible design practices, you ensure that all sighted users can read and understand your content, regardless of any visual disabilities they may have. This is especially important given that around 2.2 billion people worldwide have some form of visual disability.

Different types of visual disabilities can significantly affect how users perceive your designs. For instance, individuals with macular degeneration may have a hazy central vision, while those with cataracts might see cloudy or blurry text. Diabetic retinopathy can cause large spots on the page, and glaucoma can limit peripheral vision. These examples highlight the diverse ways in which visual impairments can impact a user’s experience.

Even though accessibility extends beyond websites, a striking statistic from WebAIM reveals the extent of the issue: they found low-contrast text on nearly 84% of the top 1 million websites’ pages, with each home page averaging 32 instances of low-contrast text.

This problem isn’t limited to those with visual disabilities; low-contrast text is challenging for everyone to read. Examples include yellow text on a white background, white text on a semi-transparent box over an image, and light green on a light blue background—all of which lack sufficient contrast.

Moreover, low-contrast text often appears on hyperlinks and buttons, making it difficult for users to read and take action. Common issues include white text on a brownish-gray background, light blue on gray, and white on yellow. Ensuring sufficient contrast not only aids readability but also helps users understand and interact with your content.

Visual disabilities can also hinder comprehension of infographics and charts. For example, a person with low vision may not see an onion in an infographic due to insufficient contrast with the background, leaving them confused about the content.

Relying solely on color to indicate hyperlinks can also be problematic, as the link may not be distinguishable from the surrounding text, especially for users with cognitive disabilities.

Colorblindness, affecting 8% of males and 0.5% of females, poses additional challenges. A donut chart designed with blue, red, green, and yellow might appear drastically different to someone with red-green or blue-yellow color blindness.

In some cases, the colors may blend, making the chart incomprehensible. For those with complete color blindness, distinguishing between similar shades of gray in a chart can be nearly impossible, further emphasizing the need for accessible design practices.

Cognitive, learning, and neurological disabilities

Accessibility in design and branding also significantly aids users with cognitive, learning, and neurological disabilities. These disabilities can include conditions such as autism, Down syndrome, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, ADHD, dyslexia, and seizure disorders like epilepsy.

Thoughtful use of color can enhance these individuals’ readability and comprehension of content. Certain color combinations have been shown to either increase or decrease readability, making it crucial to select colors that facilitate understanding. Additionally, some colors or color patterns can trigger seizures in individuals with conditions like epilepsy, underscoring the importance of careful color selection.

Why you need to consider accessibility